Melissodes rivalis

Scientific Classification

Kingdom

Phylum

Class

Order

Family

Tribe

Genus

Subgenus

Species

Binomial Name

Melissodes rivalis

Melissodes rivalis Cresson, the western thistle long-horned bee, is a specialized species of Nearctic bee native to, and occurring in, the Western United States and Southwestern Canada (Laberge, 1956a). Like all Melissodes, male M. rivalis have long antennae, and the females have short antennae in comparison (see "Genus" page for more information). This species resides in the subgenus M. (Eumelissodes) Laberge, and is closely related to M. desponsus (treated more thoroughly in “Similar Taxa”) . Both sexes of M. rivalis are somewhat distinct from other M. (Eumelissodes) Laberge, and the females can be distinguished by their often parallel inner eye portions, the dark brown to black hairs of inner surfaces of the hind bastitarsi, and the pale pubescent bands on the terga, which are often present on terga three, two, or, four, if not, then usually white pubescence is present laterally on at least one of the terga (Laberge, 1956a; Laberge, 1961). If there is still no white hairs on the terga, then females can also be distinguished by the patch of black mososcutal hairs that surpasses the size of the dark patch of hairs on the scutellum (Laberge, 1956a). Males can be distinguished from that of other M. (Eumelissodes) Laberge by their first flagellar segment, which is longer than, or equal to, two-fifths the maximum length of the second, pale pubescent bands present on terga two, three, often four, and often five, and by the clypeaus’ often darkened posterior edge (see “Description and Identification” for more information on both sexes) (Laberge, 1956a; Laberge, 1961). M. rivalis is seemingly an oligolege of the genus Cirsum, hence their common name, with the females use this plant’s pollen to provision their nests (Laberge, 1956a).

Description and Identification

Based on Laberge's (1956a) description, Melissodes rivalis are medium sized setacouse bees. Females range from 12 to 17 millimeters in length and 4.5 to 6.0 millimeters in width (width measured at the widest portion of the metasoma). Males are a bit smaller, being about 11 to 16.5 millimeters in length and 4 to 5 millimeters in width (width measured at the widest portion of the metasoma). The female's first flagellar segment is on average 2.03 times the size of the second flagellar segment (standard deviation 0.036). The males are the opposite where the second flagellar segment is on average 2.88 times the size of the first flagellar segment (standard deviation 0.062). Female wing length is 25.14 millimeters on average (standard deviation 0.339 millimeters), and male wing length is 23.94 millimeters on average (standard deviation 0.088 millimeters). Females have an average of 15.25 hamuli (standard deviation 0.367), while males have an average of 13.85 (standard deviation 0.318).

Female

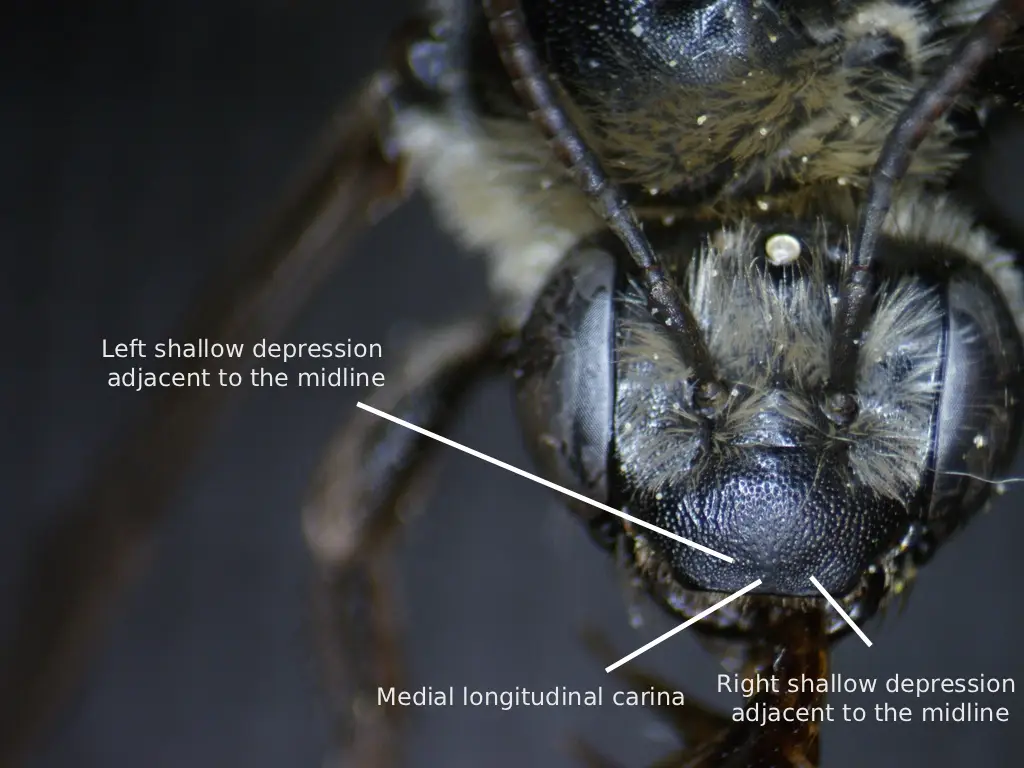

According to Laberge (1956a), the description of female M. rivalis is as follows: the integument is black, differing at the eyes, which are usually grayish blue; the wing membranes, which are infumate brown; the wing veins, which are black; the apical half of the mandibles, which are rufescent, and in the apical area of the apical half, there is a wide golden macula; the underside of flagellar segments 2-10, which are reddish brown; the distitarsi, which are dark red; the tegulae, which are piceous; and the tibial spurs, which are piceous. The surface of the clypeus is somewhat shiny, but dulled with coarse transverse shagreening, and has punctures that are small, crowded, and separated by less than one puncture diameter. The inner eye portions are parallel to one another (Fig. 1). The clypeus has a distinct longitudinal carina medially in the apical half, but also sometimes shorter (Fig. 2). The surface of the supraclypeal area is dulled with coarse reticular shagreening, and has large, deep, well-defined, round punctures. The surface of the flattened area of the vertex is shiny to moderately shiny, finely shagreened, and has deep, small, round punctures that are variably separated. In some places, the punctures are separated by less than half a puncture diameter, and in others by more than half, but less than two puncture diameters (< ½ < 2). This flattened area extends posteromedially from the apices of the compound eyes. The four maxillary palpal segments decrease in length from basal to distal in a ratio of about 3.5:2.5:2.5:1.0, and the last segment is usually even smaller. The galeae are dorsally shiny, shagreened apically and laterally, and have small widely separated punctures with small straight hairs arising from them. The mesonotum is slightly dull with fine reticular shagreening and coarsely punctate. These punctures are anteriorly and marginally separated by less than half a puncture diameter, and they’re slightly larger and sparser posteromedially, mostly separated by a minimum of two puncture diameters, in front of the posterior slope. However, the scutellum is very similar to the rest of the mesonotum, but has absent or finer shagreening. The surface of the metanotum is dulled by tessellation, and has variably spaced, scattered punctures. The propodeum’s dorsal surface is basally reticulorugose, coarsely punctate apically, and coarsely punctate on the posterior surface excluding the upper impunctate median triangle. The lateral surfaces of the propodeum are matte and dull from coarse, dense tessellation, and are coarsely punctate. The lateral surfaces of the mesepisterna are fairly dull from irregular shagreening, and have large and shallow punctures that are separated by less than half a puncture diameter. These punctures are very dense medially, with some overlapping and merging into one another, but dorsally and posteriorly, they become smaller and more distinct.

The first tergum is dull and has a latitudinal line of closely spaced punctures that appears just slightly past the middle of the tergum posteriorly. This line of punctures is separated posteriorly from the small, round, shallow, and abundant basal punctures in the medial four-fifths; punctures seemingly connect laterally (Fig. 3). The second tergum is dull and has tiny deep round punctures at the very base. The interband zone of the second tergum has small crowded lateral punctures, but is generally impunctate medially, and the apical zone of the second tergum has tiny sparse punctures laterobasally. The third and fourth terga are similar to that of the second, but the punctures are more abundant in the apical and interband zones and smaller.

Female M. rivalis can vary in setal coloration; the two extremes are as follows. The darkest specimens have black to dark brown head hairs, except for the vertex and face, which are completely pale ochraceous, and sometimes a mix of ochraceous and dark brown. Laberge (1956a) states “Metasoma with pale ochraceous hairs except as follows:...” then proceeds to list mesosomal structures. Later he states “Mesosoma with dark brown to black hairs except as follows:...” then proceeds to list metasomal structures. This is most likely a typo and will be herein treated as such. The mesosomal hairs are pale ochraceous except for the large posteromedian patch of dark brown to black hairs on the mesoscutum that usually surpasses the anterior margins of the tegulae, but usually isn’t larger than the size of the dark patch on the scutellum (Fig. 4), and the medial dark brown to black hairs on the scutellum. The tegulae and pronotal lobes have dark hairs. The general surfaces of the mesepisterna have dark brown to black hairs and the lateral surfaces have dark brown hairs on the lower two thirds and sometimes higher. The lateral surfaces of the propodeum also have dark brown to black hairs. The metasoma has dark brown to black hairs except for the basal area of the first tergum, which has long dark brown hairs, and the basal band of the second tergum, which usually has some pale hairs. The leg hairs are dark brown to black other than the ochraceous to yellow scopa, and the dark red to black hairs on the inner surfaces of the hind tibia and hind basitarsi. The palest specimens have white to grayish white head hairs, except for the vertex which has some brown hairs. The surfaces of the mesepisterna have white to pale ochraceous hairs. The pronotal lobes have white to pale ochraceous hairs. The large posteromedian patch of dark brown to black hairs on the mesoscutum reaches the middle portion of the tegula across the mesoscutum, and sometimes surpasses it. The first tergum has long pale basal hairs. The basal band of the second tergum is white, and the distal band is pale ochraceous, narrowed medially, usually interrupted medially, and does not reach the apical margin. The third and fourth tergum each have a distal pale band of pubescence, and the band of the fourth tergum is usually positioned apically. The fifth tergum has small white lateral tufts of hairs. The second, third, and fourth sterna have reddish brown hairs medially, and pale hairs apicolaterally. The inner surfaces of the fore basitarsi have red to reddish brown hairs, along with the inner surfaces of the middle bastitarsi, hind bastitarsi, and hind tibiae. The remainder of the leg hairs are black except for the ochraceous to yellow scopa.

M. rivalis ranges in setal color between these two dark and pale descriptions. As M. rivalis progressively lightens from the dark extreme to the pale extreme, pale tergal hairs start to appear. These pale hairs first develop on the base of the first and second tergum. Next, lateral pale pubescence develops on the second tergum, then the third, and subsequently the fourth. Lastly, lateral pale tufts develop on the fifth tergum. In the palest specimens, the lateral pale pubescence become complete bands, reaching completion in the same order as the appearance of the lateral pale pubescence.

Fig. 1. A comparison of the inner eye margins of a femal M. rivalis (left), and a female M. agilis (right), illustrating the parallel nature of the inner eye margins of the female M. rivalis. Photo credits: Christopher Wilson (All Rights Reserved).

Fig. 2. A labeled diagram showing the longitudinal carina of the clypeus of a female M. rivalis. Photo credit: Christopher Wilson (All Rights Reserved).

Fig. 3. A labeled diagram showing the latitudinal line of closely spaces punctures on T1 of a female M. rivalis. Photo credit: Christopher Wilson (All Rights Reserved).

Fig. 4. A labeled diagram showing the patch of dark brown to black hairs on the mesonotum of a female M. rivalis. Photo credit: Brian Dykstra (CC-BY-NC 4.0).

Male

According to Laberge (1956a), the description of male M. rivalis is as follows: the integument is black, differing at the eyes, which are green to gray; the wing membranes, which are slightly infumate and brown colored; the wing veins, which are black; the clypeus, which is paleish yellow (posterior margin of the paleish yellow area is angled upward to form an upside down V-shape in the median one-third), excluding the brownish red apical margin and the black laterobasal notches denoting the tentorial depressions (Fig. 5; in individuals from the eastern portion of its range, the posterior margin of the clypeus usually becomes infuscated from the tentorial depressions to the middle); the mandibles, which are very rarely (less than 2%) have a basal yellow macula; the labium, which very rarely has a small medial pale macula, the underside of flagellar segments 2-10, which are yellow to red; the distitarsi, which is dark reddish brown; the sterna, which are dark reddish brown; the apices of the terga, which are usually dark reddish brown; the tegulae, which are piceous; and the tibial spurs, which are piceous. The first flagellar segment’s minimum length is usually no less than one-third the maximum length of the second segment, if not more (Fig. 6). The remainder of the sculptural characteristics are similar to that of the female described above except as follows: the punctures of the clypeus are smaller and denser than that of the female; the surfaces lateral areas of the vertex are usually dull with shagreening; the first tergum’s basal four-fifths is punctate medially with small shallow punctures, and these punctures reach the apex of the tergum laterally; the second tergum’s interband zone has small punctures with undefined edges that are sometimes, be it very rarely, sparser than those of the interband zones on terga 3 and 4; the sixth sternum is shiny without shagreening, has small deep basal punctures, a distinct oblique carinae positioned laterally near the apex, a truncated apical edge, and a short median concavity positioned posteriorly in the apical half between the apices of the aforementioned carinae.

In his M. rivalis description, Laberge (1956a) wrote a comparative treatment of the male terminalia, comparing it to M. desponsus. However, the only terminalia descriptions for male M. desponsus are those of figures 114-117 from Laberge (1956b). In this current description, the male terminalia for M. rivalis will be based on figures 8-11 provided in Laberge (1956a) and figures 114-117 provided in Laberge (1956b). The seventh sternum does not narrow into a short neck, but instead is mounted to the rest of the sternum by around seven-eights of the full sternal width. This can create a notch-like structure on the lateral interior portions of the seventh sternum when looking at it dorsally. The apical half of the seventh sternum is almost two times as large as the basal half creating a fan-like shape, and has several hairs ventrally on this apical half. The 8th sternum usually has a patch of relatively long hairs apicomedially, and, at the base of this patch, the hairs shorten. The gonostylus is somewhat relatively slender with a few hairs dorsally, is less than one-half the length of the gonocoxite, and in the apical one-third, it tapers slightly. The penis valve has a prominent dorsolateral lamella; the basal end of the lamella ends in an inflected tooth.

Male M. rivalis can vary in setal coloration; the two extremes are as follows. The darkest specimens have white to pale ochraceous head hairs, except for the vertex, which has brown hairs. The mesosoma has white to ochraceous hairs except for the mesoscutum, which has a patch of dark brown hairs that reaches anteriorly past the middle of the tegulae, and the scutellum, which has some dark medial hairs. The first tergum has long basal pale hairs, and short dark apical hairs. The second tergum has a basal pale pubescent band as well as a distal pale pubescent band. The distal pubescent band is complete, medially narrowed, and separated from the apical margin. The third tergum’s distal pale pubescent band is medially interrupted with brown hairs. Terga four, five, six, and seven do not have any pale hairs. The legs mostly have pale hairs, especially on the outer surfaces of the middle and hind tibiae, except for the inner surfaces of the hind tibiae, the fore basitarsi, the middle basitarsi, and the hind basitarsi, which are red to reddish brown (Fig. 6). The palest specimens are similar to that of the darkest specimens except as follows: the hair on the head is completely white to pale ochraceous, and has no dark hairs on the vertex. The mesosoma has completely white to pale ochraceous hairs with no dark patches on the mesoscutum or the scutellum. Terga 2-5 have complete pale pubescent bands, and tergum 6 has long pale lateral tufts. Sterna 2-5 have red hairs medially, and pale ochraceous hairs laterally. The sixth sternum has entirely brown hairs. The legs have white to ochraceous hairs, except for the inner surfaces of the hind tibiae, fore basitarsi, middle basitarsi, and hind basitarsi, which are red, and the hairs on the outer surfaces of the fore tarsi and fore tibiae, which are brown.

Male M. rivalis ranges in setal color between these two dark and pale descriptions. As M. rivalis progressively lightens from the dark extreme to the pale extreme, the pale tergal hairs start to appear. These pale hairs first develop laterally on the fourth tergum. Then, lateral pale pubescence develops on the fifth tergum, and the pale band of the third tergum interrupted with brown hairs becomes complete. Next, the lateral developed pale hairs on the fourth and fifth terga meet medially creating complete bands, as this happens, the dark hairs on the head and thorax turn pale. Lastly, on the palest individuals, the dark hairs on the scutellum turn pale.

Fig. 5. A labeled diagram showing the ranging irregular clypeal marking of 2 male M. rivalis individuals. Photo credits: (right) Wendy McCrady (CC-BY 4.0); (left) Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum (CC-BY-NC 4.0).

Fig. 6. A labeled diagram showing the pubescent coloration of the legs of a male M. rivalis. Photo credit: Wendy McCrady (CC-BY 4.0).

Location and Habitat

M. rivalis is a somewhat common Cirsum oligolect occurring in the Western portions of North America. M. rivalis can be found in every U.S. state west of a longitudinal line drawn from Southeastern Texas to North-central Minnesota, as well as Southwestern Canada, and Northern Mexico (Fig. 8). Although Laberge (1956a) previously stated that M. rivalis only occurs in a range from Northern California, Southern British Columbia, Southern Manitoba, and Southern Texas, recent collections suggest that its range extends North to central British Columbia, and South to northern Mexico (Discover Life, Ascher & Pickering, 2025) (Fig. 8). M. rivalis is a highly variable species in regards to morphological traits as shown above. The following locational variability is derived from Laberge (1956a). The darkest specimens of both sexes were located in humid coastal areas of Oregon and California. These dark females are quite distinct, so much so that they were originally described as M. desponsiformis in 1905 by Cockerell (treated more thoroughly in “Taxonomy and Pylogeny”). However, the males located in this area that are assigned the “dark” variety (as this is where the dark females reside), are very similar to, and can’t be distinguished from, “paler” males located further from inland British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California. Coastal and inland specimens seemingly gradient in color across the landscape, and a discernable subspecies is likely unviable for this region. While not explicitly stated by Laberge (1956a), it is reasonable to assume specimens collected along the Rocky Mountain regions, North Dakota, Minnesota, Saskatchewan and Manitoba are somewhat lighter, possibly nearing intermediate colors of vestiture, than those of coastal populations. Although few specimens have been recorded in the following locations, both sexes of M. rivalis collected in New Mexico, Kansas, and Texas are pale and seem to be strikingly distinct from ones collected in the Rocky Mountain areas. Interestingly, females collected in Arizona are pale, similar to those collected in southeastern prairie states, and males are instead dark, similar to those collected in the Rocky Mountain areas, so much so, it’s difficult to differentiate the two. Overall, individuals residing in the upper most parts of the United States and the Southern portion of Canada, as well as Utah and Colorado are, in color, intermediate compared to the darker coastal populations of California and Oregon and the paler populations of the Southeastern prairie states. Even with this broad statement, many populations near one another differ in vestiture brightness.

Male clypeal markings differ based on location as well. Clypeal markings lighten from the darkest specimens based on the size of the posterior infuscation (i.e. the smaller the infuscation, the lighter the clypeus) in the following order: 1) Arizona, 2) Oregon, Northern California, 3) Southeastern Utah, 4) Western North Dakota, Southern Manitoba, Eastern Wyoming, Northeastern Colorado, 5) New Mexico, Eastern North Dakota, Texas, and Kansas. However, males from Southern Idaho and Northern parts of the Californian coast have predominantly pale clypei. This, along with the dark clypei of males in Arizona and Utah, is somewhat irregular as the rest of the clypei follow a smooth gradient across the landscape. Based on the range of M. rivalis, the darkest clypei of the males are located in the Northwest and the lightest in the Southeast and Northeast, with a few aforementioned irregularities. Wing and clypeal length were also measured and demonstrated to gradient across the landscape. Laberge (1956a) noted that these two measurements are highly correlated (i.e. longer wings, longer clypeus), so only wing length was described, although the clypeus follows this same pattern. Male wing length increased in mean size based on location in the following order: 1) Oregon and northern California, 2) British Columbia, North Dakota, Manitoba, Utah, Colorado, and Arizona (Texas may be included in this wing length bracket; quite a bit larger than those of Oregon and northern California), 3) New Mexico and Kansas, 4) north central Washington. Although Laberge (1956a) stated that “There seems to be an even cline in increasing male wing length toward the northeast…” This shows that the largest wing (and clypeal) lengths for males is in the northwestern portion of its range, and that there doesn’t seem to be a clearly defined locational cline in which wing length increases or decreases. These clines are quite separated and uncorrelated to the ones described above. Female wing length based on location is similar to the males, but differed in northwestern Oregon and southwestern Washington, in which the wing lengths were the smallest, higher variability in southeastern populations, and in the California and Oregon coast, where a notable abrupt shift in increased wing length (and clypeal length) occurs towards the northeast.

Fig. 8 Map showing an estimation for the known distribution for M. (Eumelissodes) rivalis. Each point represents 1 or more occurrences; occurrences that don't have coordinates are not included. Data compiled from DiscoverLife (Ascher & Pickering 2025) and GBIF (Secretariat 2023).

Fig. 9. A showing the phenological activity of M. rivalis. The x value is the month, and the y value is the number of documented observations. Data compiled from DiscoverLife (Ascher & Pickering 2025) and GBIF (Secretariat 2023).

Bionomics

Like all Melissodes, M. rivalis are ground nesting bees (Scullen, 1926). In 1926, Scullen found and documented the nesting site of M. rivalis’ (presented as M. mysops) nests. According to Scullen (1926) These nests were found on Coos Bay along the Oregon coast, located at the top of a sea clif in the side of a sand bank aggregated in a group of approximately 60 nests spanning about 20 feet. Males and females, presumably the ones within the nesting aggregation, were collected from nearby Cirsum sp. (Scullen, 1926). When two nests were opened, pollen provisions consisting of Cirsum pollen were present and eggs were not (Scullen, 1926). This implies that females provision their nests before laying eggs (like most solitary bees). Based on other species nesting accounts (M. agilis), this further implies that successful completion of egg laying is directly dependent on pollen availability. Possibly, if sufficient resources are unavailable, a female may instead choose to lay limited eggs in favor of self sustainability, although, this is speculation. Scullen (1926) stated his team made three trips were to assess nesting biology and progression. The first was made on the second of July, during which the dissected nests contained only provisions. The second trip was made July 13, during which some nests were found to have half-grown larvae, and in others, eggs had yet to hatch. Eight days later, July 21, the larvae were seemingly fully grown. Although these were separate nests each trip, most likely each with somewhat different stages of progression, it’s possible that the time from the first to last examination (19 days) represents the length during which eggs develop into fully grown larvae. This short window of development is further supported by the field note of the second trip where half-gown larvae and eggs were found in the same nests simultaneously. If the development from egg to larva occurs during this timeframe, then it’s reasonable to assume the when half-grown larvae are present, females may still be provisioning their nests and laying eggs. Although not stated in his 1926 paper, Scullen shared his field notes for publication in Laberge (1956a), and these notes, although taken by Scullen, will be herein recognized as Laberge’s paper. The nests consist of one main branch and 2-4 crooked lateral branches measuring 1-2 inches, and extending in multiple directions from this main branch approximately every one to two inches (Laberge, 1956a). At the bottom of these branches lies a cell provisioned with presumably Cirsum pollen and “honey” (although “honey” could possibly be referring to nectar instead) with one oblong egg atop the provision (Laberge, 1956a). The walls of the main branch are shiny and smooth with no discernable coating of secretion (Laberge, 1956a). A mention of one cell with an egg suspended by “web like threads” was a strange irregularity, although, as noted by Scullen, this was likely mold (Laberg, 1956). The nesting behavior presented by Scullen and his notes published in Laberge (1956) are interesting and differ from other Melissodes nesting biology. Notably, only 2-4 lateral burrows and presumably cells, were found in contrast to the 1-27 (average of 11) found for M. agilis (Parker, F. D et al., 1981). The fewer number lateral branches and cells found may be due to nest damage upon excavation, but if not, this could be a result of Coos Bay having insufficient food resources. Resulting in female M. rivalis unable to provision many cells. The only note pertaining to a parasite of M. rivalis is the possibility of Triepeolus paenepectoralis (Lopez, 2017).

Flower records

All flower records included in this list are from reports in the literature. Each flower has a parenthesized reference listed after it, corresponding to the literary work in which it was recorded. Apocynum sp. (Laberge, 1956a), Asclepias sp. (Laberge, 1956a), Aster sp. (Bohart et al., 1973), Carduus sp. (Laberge, 1956a; originally presented as “Carduus aculescens”, however, this name cannot be found to be a valid or synonymous name in any taxonomic databases), Cirsium sp. (Laberge, 1956a), Cirsium arvense (Laberge, 1956a), Cirsium brevifolium (Hawse, 2024), Cirsium douglasii (Lopez, 2017), Cirsium engelmannii (Laberge, 1956a), Cirsium occidentale (Lopez, 2017), Cirsium pumilum (Laberge, 1956a), Cirsium undulatum (Laberge, 1956a), Cirsium vulgare (Laberge, 1956a), Grindelia platyphylla (Laberge, 1956a), Helianthus annuus (Laberge, 1956a), Monardella sheltonii (Lopez, 2017), Penstemon sp. (Laberge, 1956a), Penstemon cyananthus (Laberge, 1956a), Petrophytum sp. (Bohart et al., 1973), Plectocephalus americanus (Laberge, 1956a), Rudbeckia sp. (Laberge, 1956a), Solidago sp. (Laberge, 1956a), Solidago glutinosa (Bohart et al., 1973), Teucrium sp. (Laberge, 1956a), Trifolium pratense (Laberge, 1956a), Trifolium repens (Laberge, 1956a), Verbena sp. (Laberge, 1956a).

Taxonomy and Phylogeny

M. rivalis was originally described from five male specimens in 1872 by Ezra Townsend Cresson. When first described, M. rivalis was given no subgenus as none had been proposed. These specimens, collected by Gustaf Wilhelm Belfrage and Jacob Boll, were found in Texas. Within the description, Cresson (1872) described male M. rivalis as having “head and thorax clothed with a dense whitish pubescence,” and “each (abdominal) segment with a sub apical fasciae of short appressed whitish pubescence…” With these specimens being collected in Texas (Cresson, 1872), it’s unsurprising that they follow the pale description above, having all terga bare white pubescence and light hairs on the vertex of the head. In June of 1905, Theodore Dru Alison Cockerell described M. rivalis under the name “Melissodes mysops” from one male and three females (Cockerell, 1905a). The description of the male states that the “clypeus lemon-yellow, its upper margin black,” and “scutellum with black hairs in middle…abdomen narrower and longer (than M. cnici; now M. desponsus), with weak light hair-bands, failing in the middle” (Cockerell, 1905a). This matches quite well with the intermediate description of male M. rivalis, which makes sense, as the specimens were collected in Colorado. The female description mirrors this as well with the statements “distinct pale hair-bands, especially on the third and fourth (abdominal) segments,” and “apex of abdomen (has) dark fuscous or black (hairs)” (Cockerell, 1905a). This is likely referring to the “fourth step” of lightening where lateral pale pubescence is apparent on terga 2-4, but no lateral pale lateral tufts have developed on T5. In September of 1905, Henry Louis Viereck et al. described M. rivalis under the name “Melissodes desponsiformis” from a female. This description compared M. desponsiformis to M. mysops using characters such as “palest on vertex…cheeks with black or sooty hair” for M. desponsiformis and “cheeks with yellowish-white or grayish-white hair” for M. mysops (Viereck et al., 1905). This is seemingly comparing a darker M. rivalis specimen (M. mysops), having darker ochraceous head hairs, to the lighter specimen (M. desponsiformis), having lighter pale hairs. M. desponsiformis is also described as having “hairbands on segments 3 and four, and a line on each side of two” (Viereck et al., 1905). This is strange as the progression of hair bands is off according to Laberge’s (1956a) description, although, individuals will vary and this seems to be a representation of a somewhat intermediate coloration, which makes sense as the female M. desponsiformis was found from inland Oregon, not coastally. In October of 1905, Cockerell described M. hexacantha and M. nigrosignata in the same article as two separate species based on three M. hexacantha males and two M. nigrosignata females all of which were collected in Arizona (Cockerell, 1905b). The two cannot be compared because of the different sexes, but descriptions can be compared to those of female and male M. rivalis to see what portion of the cline they belong. Both of these specimens were described to have bands of pubescence on terga 2-4, M. hexacantha having “not defined basal one on two,” and M. nigrosignata having “an entire basal band (on T2) and a broadly interrupted median one” (Cockerell, 1905b). These “two species” also had the hairs on terga five and six dark with M. nigrosignata having “black hair, long white hair showing at extreme sides of the fifth,” and M. hexacantha having “chocolate-color (hairs). (Cockerell, 1905b)” Cockerell made a note in the description of M. nigrosignata of how this “species” can be distinguished from that of M. mysops by the light lateral thoracic hairs, and the “bicolored middle tibiae.” As M. nigrosignata was found in Arizona (Cockerell, 1905b), it makes sense that this specimen would fall into the paler category, not the palest, but nearing so. M. hexacantha, also found in Arizona (Cockerell, 1905b), seems to be somewhat darker with statements such as "mesothorax (hairs) black,” and “vertex with very few black hairs at sides.” This also makes sense as Arizona is one of the setal coloration cline irregularities, where females are light and males are darker (Laberge, 1956a). However, there are still light somewhat defined bands on terga 3 (darkest specimens have this) and 4, though this just "step 1" as no white hairs were visible laterally on the fifth tergum. Very little is accessible in regards to the description of M. habilis, although what is stated is that a variation found from a male specimen in Colorado has an almost non-existent pale band on the fourth tergum (Cockerell, 1937). Showing this may be one of the darkest specimens. The substantial differences in setal colorations across the landscape are most likely what lead to the many redescriptions of M. rivalis. Laberge found that the distinctions each of these authors made based on setal differences were actually individual-to-individual intraspecific variations occurring due to a cline in color across the landscape, and not clear-cut separate species (Laberge, 1956a). Based on the code outlined by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, section 23.1 states that if the valid name of a taxon should be the oldest one (i.e. M. rivalis as it was published in 1872). As M. rivalis has been described under multiple different names, those respective names are appointed junior objective/subjective (case dependent) synonym status, and M. rivalis becomes the senior synonym (ICZN).

When redescribed in his second revision, Laberge (1956a) assigned M. rivalis to the subgenus M. (Heliomelissodes) Laberge. This subgenus only included two species, those being M. rivalis and M. desponsus, with M. desponsus as the type species (Laberge, 1956a). These two species are both oligolects of Cirsum. Males of this subgenus have distinctly long first flagellar segments, and distinctly short second ones while females have parallel inner eye margins (Laberge, 1961). However, in 2023, a revision of the tribe Eucerini, in which Melissodes reside, synonymised Heliomelissodes with the subgenus M. (Eumelissodes) Laberge, due to the presence of M. (Heliomelissodes) Laberge rendering M. (Eumelissodes) Laberge paraphyletic (Freitas et al., 2023; Wright et al., 2020). These species, M. rivalis and M. desponsus, are quite distinct within M. (Eumelissodes) Laberge, and do not specifically resemble any other M. (Eumelissodes) Laberge besides from one another (see more in “Similar Taxa”).

Similar Taxa

As previously stated, M. rivalis and M. desponsus form somewhat of a clade within their subgenus. Both species are separated largely in range, M. rivalis being westwars, and M. desponsus eastward. However, darker specimens of M. rivalis can resemble M. desponsus. Although M. rivalis’ description has already been treated above, a subsequent comparison of the two may shed light on some important differences. Both species share a very similar phenology and flower preference (Cirsum), with peak activity occurring around July and August (see Fig. 9) (Laberge, 1956; GBIF Secretariat, 2023). Although the greatest distinguishing factor between M. rivalis and M. desponsus is seemingly their locality, distinctions in their morphology are important identifiers. All descriptions listed below are derived from Laberge (1956a).

Female

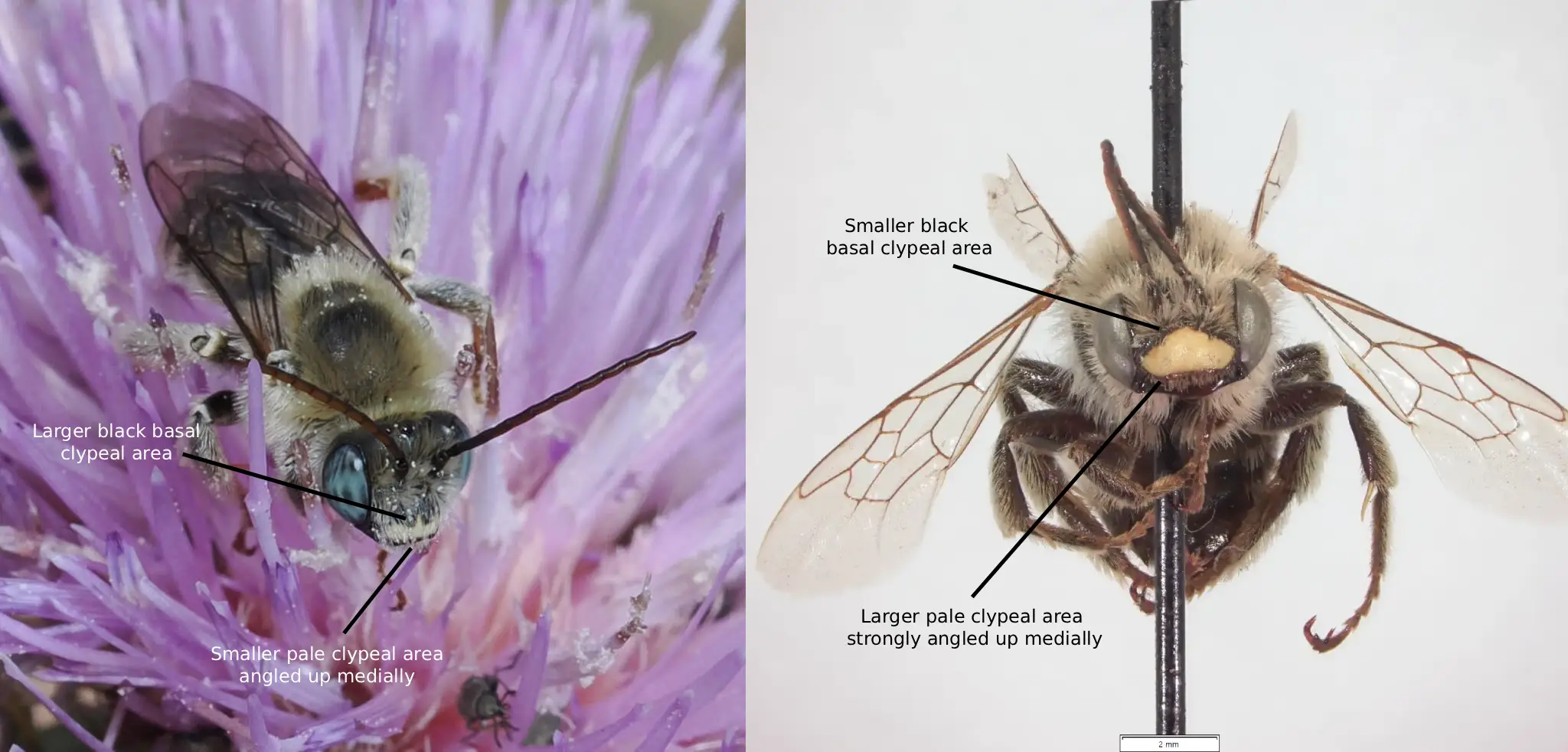

The eyes of M. rivalis are often grayish blue, whereas in M. desponsus, the eyes are grayish blue to green. The wing membranes of M. agilis are infumate with distinct brown coloring, whereas in M. desponsus, the wing membranes are infumate with less distinct brown coloring. The apical margin of the clypeus of M. rivalis is black, whereas in M. desponsus, it’s usually rufescent. The clypeus of M. rivalis has a distinct longitudinal carina medially in the apical half, but also sometimes shorter, and the surface has crowded, irregular punctures. Whereas in M. desponsus, the punctures are more “normal” and there is no defined medial carina (Fig. 10). The punctures on the posteromedian area of the mesoscutum of M. rivalis are sparse, mostly separated by 2 puncture diameters, sometimes more. Whereas in M. desponsus, the punctures are separated by slightly more than half a puncture diameter.

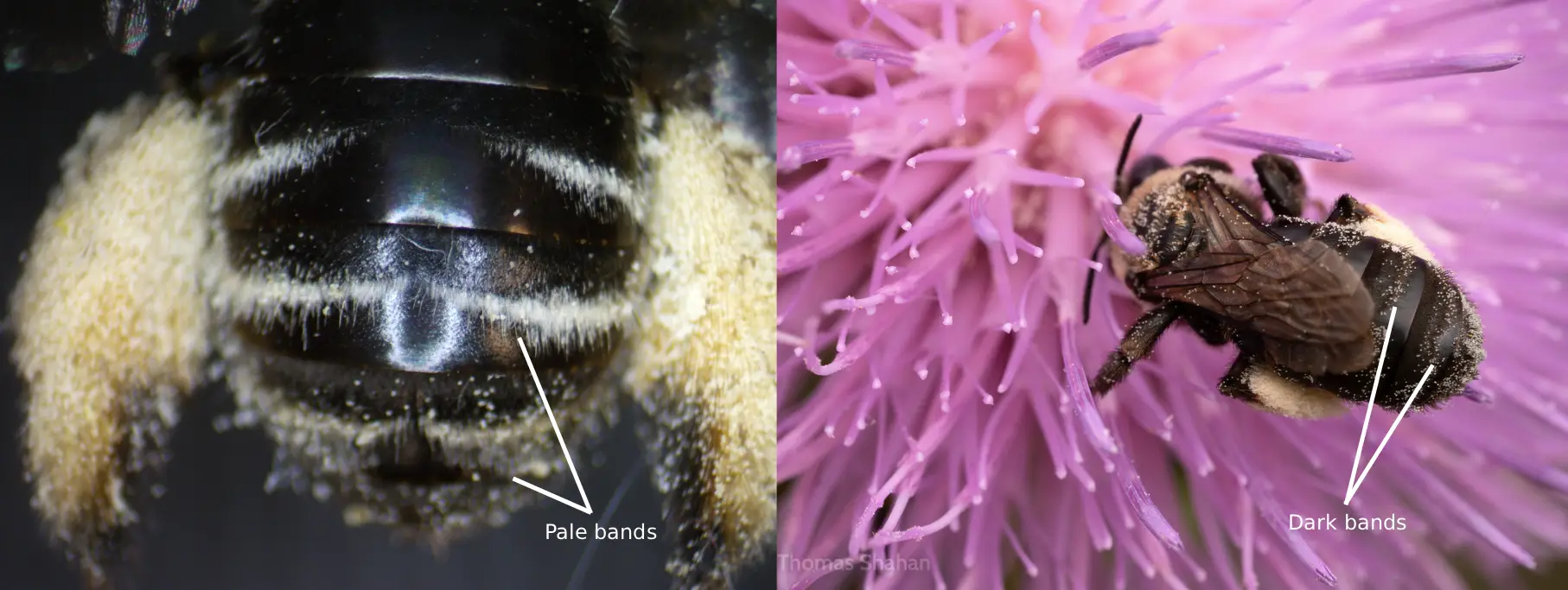

Setal differences are as follows: The darkest M. rivalis have a large patch of dark hairs on the mesonotum that usually surpasses the anterior margins of the tegulae, if not, then at least reaches them. Whereas in M. desponsus, the mesoscutum usually has a small patch of dark hairs, but this patch never reaches the median of the tegula, and very rarely exceeds the size of the small dark patch on the scutellum (Fig. 11). M. rivalis has the mesonotal patch of dark hair almost covering the entire scutellum, whereas in M. desponsus, the scutellum has a very small patch of dark hair medially (Fig. 11). M. rivalis has dark hairs on the lower two-two thirds of the mesepisterna and sometimes more, whereas in M. desponsus, the dark hairs are present at least on the lower one-half and sometimes more. M. rivalis have dark hairs on the pronotal lobes and tegulae, whereas in M. desponsus, the hairs are pale ochraceous. The hairs on the first tergum of M. rivalis are long and brown, whereas in M. desponsus, the hairs are pale ochraceous, and usually mixed with a few dark hairs, on the basal three-fifths. The hairs on the inner surfaces of the hind tibia and hind bastitarsi of M. rivalis are dark red to black. Whereas in M. desponsus, the inner surfaces of the hind tibiae are red to yellow, and the inner surfaces of the hind bastitarsi are dark brown to black. The pale M. rivalis have grayish white to white hairs on the head with a few brown on the vertex, whereas in M. desponsus, the hairs are completely pale ochraceous and sometimes ochraceous with brown hairs. M. rivalis has white to pale ochraceous pronotal and mesepisternal hairs, whereas in M. desponsus, these hairs are dark brown to black on the bottom half of the mesepisterna, sometimes higher, and pale ochraceous on the pronotum (Fig. 12). M. rivalis has a large patch of dark hairs on the mesonotum that usually reaches the middle of the tegulae, sometimes surpassing them (extends anteriorly slightly less than dark M. rivalis). Whereas in M. desponsus, the mesoscutum usually has a small patch of dark hairs, but this patch never reaches the median of the tegula, and very rarely exceeds the size of the small dark patch on the scutellum. The first tergum of M. rivalis has long basal pale hairs, whereas in M. desponsus, the hairs are white to pale ochraceous, and often have some darker hairs mixed in. The second tergum of M. rivalis has a white basal band, and a pale ochraceous distal band that is medially narrowed and usually interrupted medially. Whereas in M. desponsus, the basal band has some pale pubescence, but the distal band is dark brown to black (Fig. 13). The third and fourth terga of M. rivalis have distal bands of pale pubescence (the band on the fourth tergum positioned apically), whereas in M. desponsus, these bands are dark brown to black (Fig. 14). The fifth tergum of M. rivalis has small white lateral tufts of hairs, whereas in M. desponsus, the fifth tergum is fully dark brown to black. Sterna 2, 3, and 4 of M. rivalis have pale apicolateral hairs and reddish brown medial hairs, whereas in M. desponsus, these hairs are dark brown to black. The inner surfaces of the fore basitarsi of M. rivalis have red to reddish brown hairs, along with the inner surfaces of the middle bastitarsi, hind bastitarsi, and hind tibiae. Whereas in M. desponsus, the inner surfaces of the hind tibiae are red to yellow, and the inner surfaces of the fore bastitarsi, middle bastitarsi, hind bastitarsi, and hind tibiae are black.

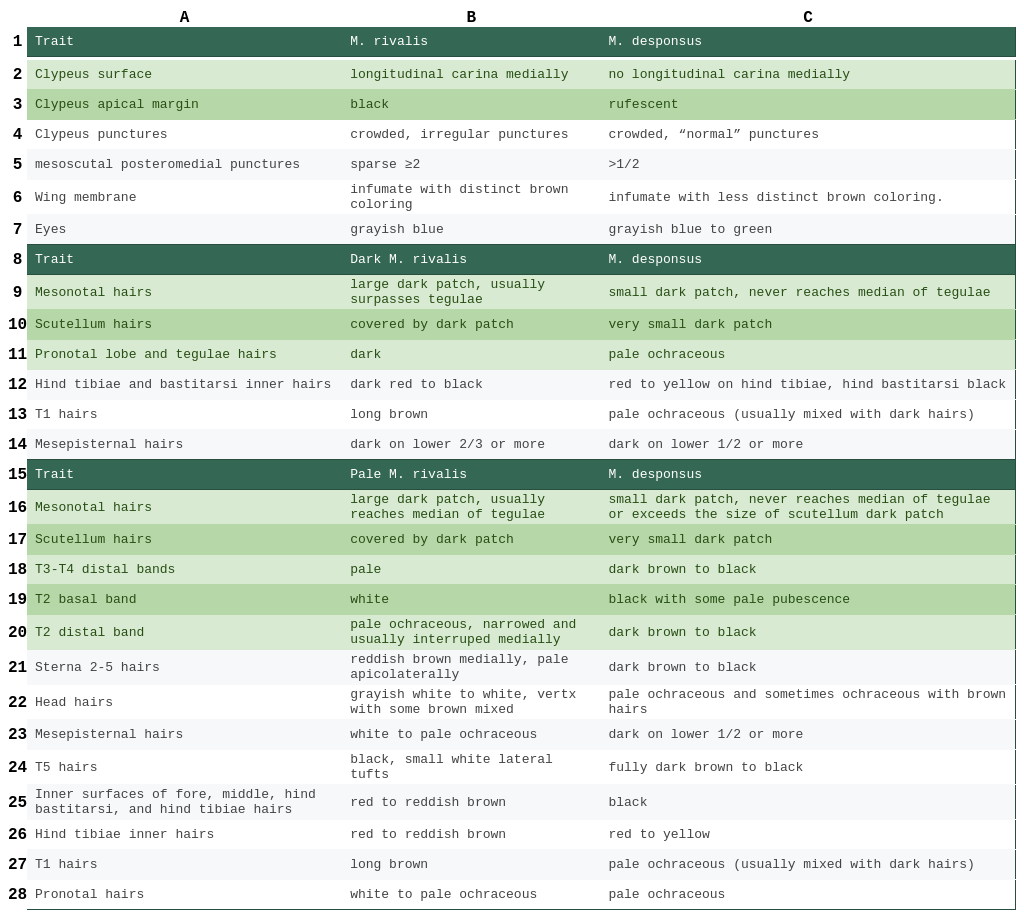

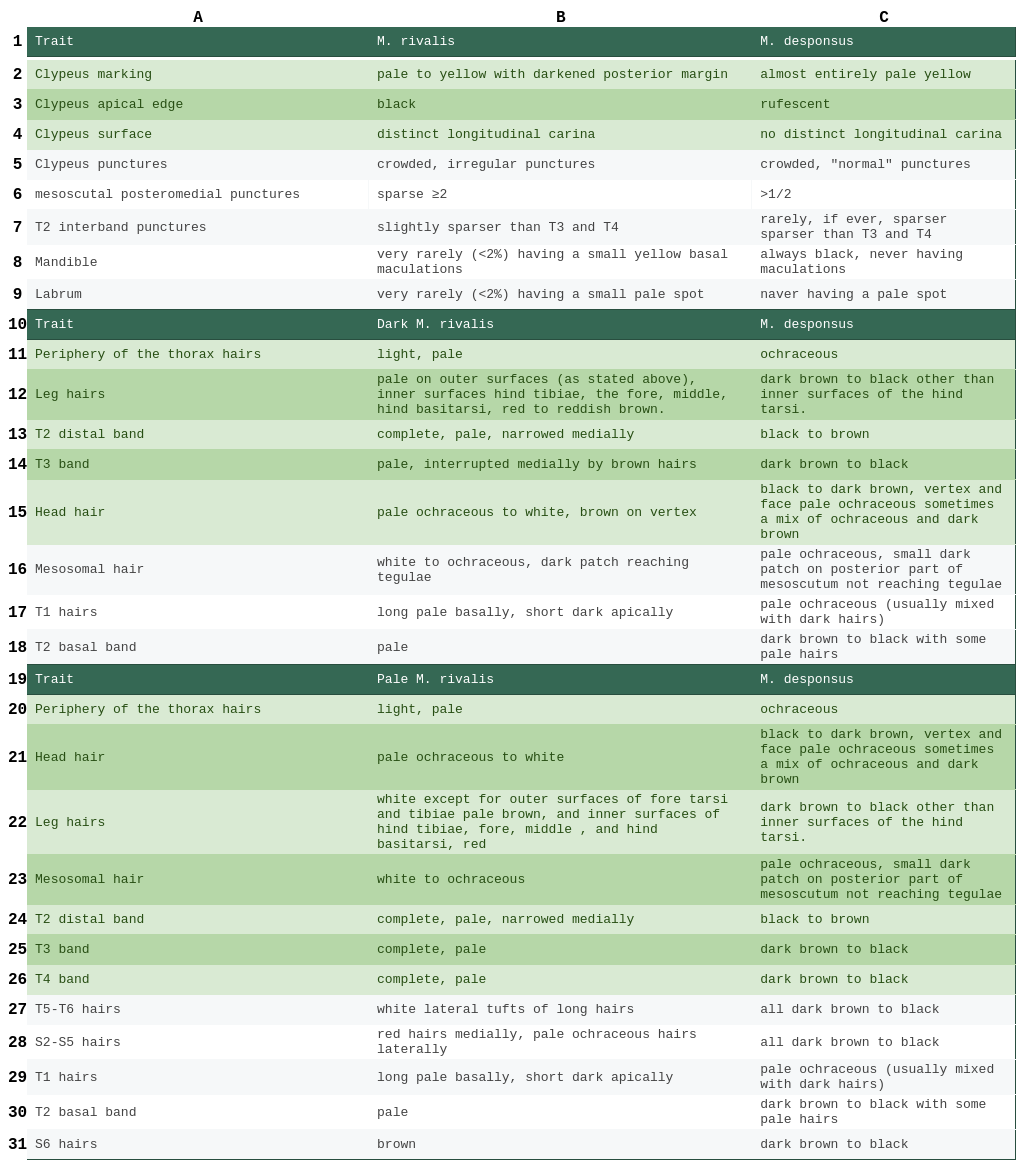

Table 1. A comparison of trait differences between female M. rivalis and M. desponsus. The traits are sorted from most to least diagnostic. Traits highlighted in green are the most important traits when comparing between M. rivalis and M. desponsus. Traits not explicitly referring to hair refer to integument. Three seperate sections of the table are given 1) integument comparison 2) dark M. rivalis comparison 3) pale M. rivalis comparison. Each of these sections follow the pattern listed above respectivly.

Fig. 10. A comparison of the clypeus of the females of M. rivalis (left) and M. desponsus (right). Photo credits: (left) Christopher Wilson (All Rights Reserved); (right) Isabel Dalton (All Rights Reserved).

Fig. 11. A comparison of the mesonotum of the females of M. rivalis (left) and M. desponsus (right). Note, this M. rivalis specimen is dark. Photo credits: (left) Brian Dykstra (CC-BY-NC 4.0); (right) Heather Holm (CC-BY-NC 4.0).

Fig. 12. A comparison of the lateral thoratic hairs of the females of M. rivalis (left) and M. desponsus (right). Note, this M. rivalis specimen is pale. Photo credits: (left) Christopher Wilson (All Rights Reserved); (right) Heather Holm (CC-BY-NC 4.0).

Fig. 13. A comparison of the bands of the second tergum of the females of M. rivalis (left) and M. desponsus (right). Note, this M. rivalis specimen is pale. Photo credits: (left) Christopher Wilson (All Rights Reserved); (right) Stephen Barten (All Rights Reserved).

Fig. 14. A comparison of the bands on terga 3 and 4 of the females of M. rivalis (left) and M. desponsus (right). Note, this M. rivalis specimen is pale. Photo credits: (left) Christopher Wilson (All Rights Reserved); (right) Thomas Shahan (CC-BY-NC 4.0).

Male

The mandibles of M. rivalis rarely have a small yellow basal maculation, and the labium very rarely has a pale spot. Whereas in M. desponsus, the labrum and mandibles never have maculations. The clypeus of M. rivalis has a darkened posterior margin, usually with the posterior one-third to one-half darkened very rarely ever more than that (clypeus never fully black) and the apical edge is black; posterior yellow area angled upward medially to form almost and upside down “V”. Whereas in M. desponsus, the clypeus is almost entirely pale yellow with a rufescent apical edge (Fig. 15). The clypeus of M. rivalis has a distinct longitudinal carina medially in the apical half, but also sometimes shorter, and the surface has crowded, irregular punctures. Whereas in M. desponsus, the punctures are more “normal”, smaller and denser than the female’s clypeal punctures, and there is no defined medial carina. The punctures on the posteromedian area of the mesoscutum of M. rivalis are sparse, mostly separated by 2 puncture diameters, sometimes more. Whereas in M. desponsus, the punctures are separated by slightly more than half a puncture diameter. The punctures in the interband zone of the second tergum of M. rivalis usually have slightly sparser punctures than the interband zones of terga three and four, whereas in M. desponsus, the punctures are rarely, if ever, sparser.

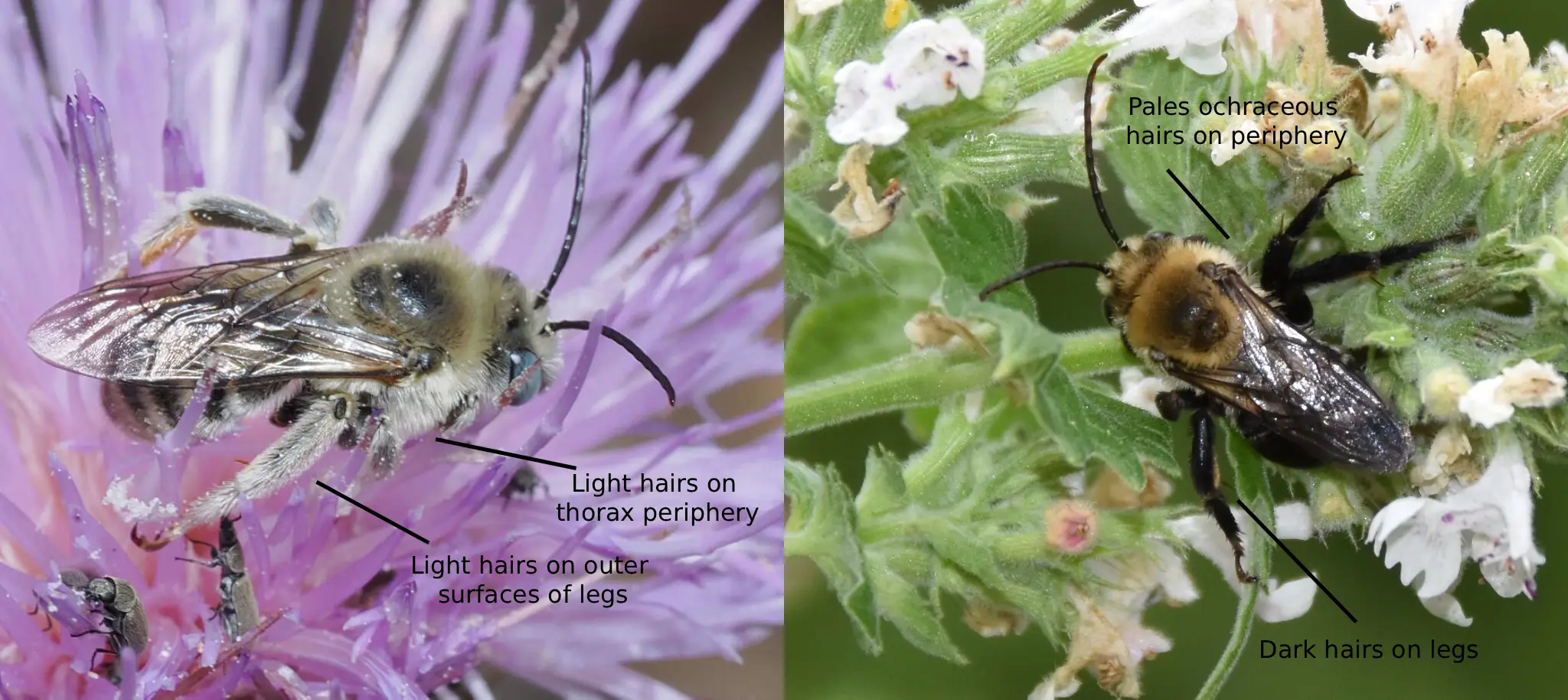

Setal differences are as follows: Generally, M. rivalis is significantly lighter than M. desponsus, especially on the outer surfaces of the legs and periphery of the thorax (Fig. 16). The dark M. rivalis has pale ochraceous to white head hair, excluding the hairs on the vertex, which are brown. Whereas in M. desponsus, the hairs on the head which are black to dark brown, except for the vertex and face, which are completely pale ochraceous, and sometimes a mix of ochraceous and dark brown. The mesosoma of M. rivalis has white to ochraceous hairs, except for the mesonotum which has a posteromedial dark patch of hairs that reaches anteriorly to the middle of the tegulae and sometimes beyond (dark patch on scutellum medially and on mesoscutum posteriorly). Whereas in M. desponsus, the mesonotal hairs are mostly pale ochraceous except for the usually present posteromedian patch of dark brown to black hairs on the mesoscutum that doesn’t surpass the tegulae, and usually isn’t larger than the small patch on the scutellum. The scutellum also has a small patch medial dark brown to black hairs. The first tergum of M. rivalis has long pale basal hairs and short dark apical hairs, whereas in M. desponsus, these hairs are white to pale ochraceous and often mixed with darker hairs. The second tergum has a basal pale band and a complete pale distal band that narrows medially. Whereas in M. desponsus, the basal pale band is mostly dark brown to black with some pale hairs, and the distal band is black to brown. The third tergum of M. rivalis has a distal pale band that gets interrupted medially by brown hairs, whereas in M. desponsus, this band is dark brown to black. The legs of M. rivalis have pale hairs, especially on the outer surfaces, except for the inner surfaces of the hind tibiae, the fore basitarsi, the middle basitarsi, and the hind basitarsi, which are red to reddish brown. Whereas in M. desponsus, the legs have dark brown to black hairs other than inner surfaces of the hind tarsi. The pale M. rivalis follow this same pattern, except as follows: there are no dark hairs on the head; the mesoscutum and or scutellum do not have dark patches; terga 2-4 have pale bands and terga 5-6 have lateral tufts of white long hairs (Fig 17); sterna 2-5 have red hairs medially and pale ochraceous hairs laterally, and sternum 6 has brown hairs; legs completely white except for the outer surfaces of the fore tarsi and fore tibiae, which are pale brown, as well as the inner surfaces of the hind tibiae, fore basitarsi, middle basitarsi, and hind basitarsi, which are red.

Table 2. A comparison of trait differences between male M. rivalis and M. desponsus. The traits are sorted from most to least diagnostic. Traits highlighted in green are the most important traits when comparing between M. rivalis and M. desponsus. Traits not explicitly referring to hair refer to integument. Three seperate sections of the table are given 1) integument comparison 2) dark M. rivalis comparison 3) pale M. rivalis comparison. Each of these sections follow the pattern listed above respectivly.

Fig. 15. A comparison of the clypei of male M. rivalis (left) and M. desponsus (right). Photo credits: (left) Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum (CC-BY-NC 4.0); (right) iNaturalist username: hobiecat (CC-BY-NC 4.0).

Fig. 16. A comparison of the general leg and thoratic periphery coloration of male M. rivalis (left) and M. desponsus (right). Note, this M. rivalis specimen is pale. Photo credits: (left) Wendy McCrady (CC-BY 4.0); (right) Richard Baxter (CC-BY-NC 4.0).

Fig. 17. A comparison of the bands of the terga of male M. rivalis (left) and M. desponsus (right). Note, this M. rivalis specimen is pale. Photo credits: (left) Wendy McCrady (CC-BY 4.0); (right); Josh Klostermann (All Rights Reserved).

However, with all of this said, a newer report of bees in Minnesota suggests that these characteristics listed by Laberge (1956a), may not be as diognotic as previously thought (Portman et al., 2023). As stated by Portman et al. (2023) "Melissodes was last revised over 60 years ago (LaBerge 1956a, 1956b, 1961) and contains multiple species that need to have their taxonomic status clarified (such as M. desponsus and M. rivalis)." This suggests that populations of M. rivalis and M. desponsus that are largely seperated may exhibit these characters as described by Laberge (1956a), but populations with overlapping ranges (such as the ones found in Minnesota), may exibit traits outside of the descriptions Laberge (1956a) presented.

Literature Cited

1. Ascher, J.S. & Pickering, J. (2025). Discover Life bee species guide

and world checklist (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila): Data records. Discover Life. Available at:

https://www.discoverlife.org/mp/20q?guide=Apoidea_species (Accessed 08 November 2025).

2. Bohart, George E. and Knowlton, G. F., "The Bees of Curlew Valley (Utah and Idaho)" (1973). All PIRU

Publications. Paper 790. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/piru_pubs/790

3. Cockerell, T.D. (1905a) "New and Little-Known American Bees." The Entomologist, 38(505), pp. 145–149. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/25338093

4. Cockerell, T.D. (1905b) ‘Some new eucerine bees from the West’, Psyche: A Journal of Entomology, 12(5), pp. 98–105. doi:10.1155/1905/73160.

5. Cresson, E. T. (1872). Hymenoptera texana. American Entomological Society. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.9428

6. Freitas, F.V. et al. (2023) ‘UCE phylogenomics, biogeography, and classification of long-horned bees (hymenoptera: Apidae: Eucerini),

with insights on using specimens with extremely degraded DNA’, Insect Systematics and Diversity, 7(4). doi:10.1093/isd/ixad012.

7. GBIF.org (08 November 2025) GBIF Occurrence Download, DOI available at time of access: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.jghu9p.

Archive preserved at Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.175606262

8. International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN). 1999. International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (Online). Edited by Ride, W.D.L.,

Cogger, H.G., Dupuis, C., Kraus, O., Minelli, A., Thompson, F.C. & Tubbs, P.K. International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature.

Available at: https://code.iczn.org/ (Accessed: 15 November 2025)

9. LaBerge, W.E. (1956a) ‘A revision of the bees of the genus melissodes in north and

Central America. part II (hymenoptera, Apidae)’, The University of Kansas science

bulletin, 38(8), pp. 533–578. doi:10.5962/p.376392.

10. LaBerge, W.E. (1956b) ‘A revision of the bees of the genus melissodes in north and Central America. part I.

(Hymenoptera, Apidae)’, The University of Kansas science bulletin, 37(18), pp. 911–1194. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.24549.

11. LaBerge, W.E. (1961) ‘A revision of the bees of the genus melissodes in north and Central America.

part III (hymenoptera, Apidae)’, The University of Kansas science bulletin, 42(5), pp. 283–663.

doi:10.5962/bhl.part.9821.

12. Lopez, C. (2017) THE BEE FAUNA OF THE HORSE MOUTAIN AND GROUSE MOUNTAIN REGION, HUMBOLDT COUNTY, CALIFORNIA. thesis. Humboldt State University.

13. Scullen, H. A, (1926). MELLISSODES MYSOPS COCKERELL NESTING IN

OREGON (ANTHOPHORIDAE, HYM.) Pan-Pacific Entomologist, 4(4), 176.

13. Parker, F. D., Tepedino, V. J., & Bohart, G. E. (1981). Notes on the Biology of a Common Sunflower Bee, Melissodes

(Eumelissodes) agilis Cresson. Journal of the New York Entomological Society, 89(1), 43–52. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25009235

14. Viereck, Henry. et al. (1906) ‘Synopsis of bees of Oregon, Washington, British Columbia and vancouver—V.’, The Canadian Entomologist, 38(9), pp. 297–304. doi:10.4039/ent38297-9.

15. Cockerell, T.D. (1937) "New and Little-Known American Bees." American Museum Novitates, 899, pp. 5.

16. Hawse, A.R. (2024) Patterns of Bee Diversity and Plant-Pollinator Interactions in the Palouse Prairie. thesis. University of Idaho.

17. Portman, Z. M. et al. (2023): A checklist of the bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of

Minnesota. Zootaxa 5304 (1): 1-95, DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.5304.1.1, URL:

http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5304.1.1

18. Wright, K.W., Miller, K.B. and Song, H. (2020) ‘A molecular phylogeny of the long-horned bees in the genus

Melissodes latreille (hymenoptera: Apidae: Eucerinae)’, Insect Systematics & Evolution, 52(4), pp.

428–443. doi:10.1163/1876312x-bja10015.